December 2002-February 2003

By Glenn H. Mullin

Photo © Jirina Simajchlova / Tibet Images

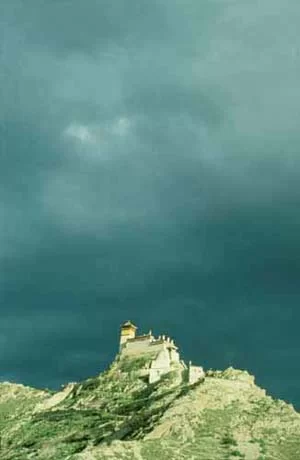

Yumbulhakang, reputedly the castle of the first Tibetan king, Nyatri Tsenpo, ornaments the Yarlung Valley. Photo © Jirina Simajchlova / Tibet Images.

A few years ago I was speaking with a Tibetan friend living in Canada, when the topic of life as a refugee in a foreign land came up. He, like most Tibetans living abroad, had left his homeland several decades earlier because of the Chinese Communist invasion of Tibet. I asked him what he missed most about the old country.

“Khorwa,” he replied. “The walk-around. Over here there is nothing even slightly resembling it. For us, the morning and evening walk-arounds of our local sacred sites were highlights in our day. In addition, we would make occasional walk-arounds to more remote sacred places, and once a year undertake an even more distant one. And then there were the once in a lifetime walk-arounds, when we went to remote places like Mt. Kailash and Lhamo Latso, the Oracle Lake.”

Anyone who has lived with the Tibetans in Asia can relate to his nostalgia. One is usually awakened at five in the morning by the sound of feet scurrying along the roads and paths, and the hum of prayers being quietly recited to the rhythm of turning mantra wheels. It is long before sunrise, but everyone is wide-awake and off to their favorite local walk-around.

When I lived in Dharamsala, for example, the favorite was the two-mile path that began in the village, circled the stupa in the center of town, ran down to the left past the Tsennyi Labtra, circled the mountain on which the Dalai Lama’s house stands, came back around the mountain to the Namgyal Dratsang Monastery, and returned to the village from there.

The path circling the mountain was especially significant to those who used it regularly, for every nook and cranny had its own story to tell. A small stupa at one place contained tsa-tsa with ashes of a deceased friend; at another stood a flat mantra stone that was once offered to celebrate a child’s birth; and at another was a hut filled with small clay statues, reminding everyone of the year the Nechung Oracle had warned of a danger to the Dalai Lama’s life, and recommended that the Tibetan community collectively accumulate tens of millions of mani mantras as a means of eliminating the hindrance.

Some people walked alone while doing this khorwa, using the time period for private thoughts and reflections, reciting their prayers and mantras as they went. Others walked in small groups: family or friends sharing a few spiritual moments together, chatting and perhaps even giggling and gossiping as they went. Young people walked, some meditatively and others simply hoping to capture a furtive glimpse of a potential lover. Falling in love is always wonderful, but falling in love at a sacred place is especially auspicious. And the very old hobbled around the path on their canes, hoping to generate a bit more merit and wisdom before the Lord of Death came calling.

This same ritual was repeated at the end of the day, although this time more leisurely. The early morning khorwa had been conducted with a pressed intensity, for everyone had to get back for the long day’s work. The evening event was more of a celebration and an unwinding.

Every city and village in Tibet had its local walk-around. Larger cities such as Lhasa had a number of them: short neighborhood walk-arounds that became interconnected for longer khorwa on especially auspicious days, such as Saka Dawa or Ganden Namchu.

However, whereas the khorwa in Dharamsala tells the story of the Tibetans in exile from the early 1960s until the present time, and only carries a significance that operates within this very limited dateline, the sites in Tibet are repositories of knowledge going back to ages before written history began. This knowledge is not mere information, such as a list of famous people who had meditated there or visited the place at some time or another, but is a force that operates simultaneously on a number of dimensions …

Read the complete article as a PDF Download.

https://fpmt.org/mandala/archives/mandala-issues-for-2002/december/the-secret-life-of-power-places/

The Secret Life of Power Places - FPMT

PILGRIMAGE December 2002-February 2003 By Glenn H. Mullin A few years ago I was speaking with a Tibetan friend living in Canada, when the topic of life as a refugee in a foreign land came up. He, like most Tibetans ... Read more »

fpmt.org

'Post' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Remarkable Meetings with Lama Yeshe: Encounters with a Tibetan Mystic (0) | 2022.08.21 |

|---|---|

| War and Peace in Tibetan Buddhism (0) | 2022.08.20 |

| Max, Priya, Glenn, Roberta, Tushita, 1977 (0) | 2022.08.18 |

| Lama Glenn Mullin - Buddhist Pilgrimage to the Power Places of Nepal | Wisdom Keeper E2 (0) | 2022.08.17 |

| Sacred Music and Dance Promotes Dharma (0) | 2022.08.10 |